I would rather die than come up with words to comfort a grieving person. But I have to. Now.

Fatim’s round face and curled-up lips tell a story of strength—a girl who can smile and get through school, despite tragedy. It says: Niko ubuzima bugenda. That’s how life goes. She could’ve skipped today’s exam, but she didn’t. She could’ve gone back home to Pointe-Noire, but she didn’t. She could’ve curled up in bed and told me to foute le quand! But she didn’t.

Instead, we’re sitting on the stairs along the U.S. Embassy’s fence. Eating cookies.

——–

For the past few days, our favorite hobby has been walking around the neighbourhood, talking about anything. So when I showed up on her doorstep with a paper bag holding two mangoes, it wasn’t out of the ordinary for Fatim to suggest a walk first.

I stand in the courtyard overlooking Nyarugenge, with its emerging cityscapes—every Kigalian photographer’s wet dream. The evening is warm, still, and quite dark. Yet I can feel the slightest shift in the air. The smell of humid clouds. But there’s none in the sky. The girls next door are starting to cook something—onion and garlic. A black cat lies in the driveway. A typical night in Kigali. And a normal walk.

So why is my throat dry tonight?

I saw Fatim earlier, rushing to class in her bronze veil, black trousers, and, as always, wearing those black Sambas. I was late for Bible study; she was probably late for econ class too. But she’d promised to teach me a mango recipe, and I was eager to stop eating the same old oatmeal yogurt.

I got the mangoes and walked home with a quicker stride than usual. Spices? Sugar? And salt — all in the same bowl as mangoes? Her self-satisfied grin said it all—this was a tried-and-true method where she’s from. If other Africans love it, I probably will. I always think of myself as a son of the motherland.

A click behind me brings me back to the courtyard.

“We go?”

“Oui“

“You have les cles for the gate.”

“Non. You?”

“Let me grab them.”

I step inside my house and look for my keys. They should be on the table. Nothing. Cupboard? Bedside? Still nothing. You’d think in a studio apartment everything would be within arm’s reach. But honestly, if I don’t see something for more than a minute, it might as well not exist. Which is why I sleep in an unlocked house at least three nights a week.

As I’m losing my mind, uncontrollable laughter erupts behind me, growing louder. I step back out.

“What’s so funny?”

Her eyes flash a meter beside me, then she bursts into laughter again. I check the door. There are my keys and flash drive on a ring, dangling.

Definitely not amusing.

I head for the gate. Fatim follows, still chuckling. As soon as we step out, she says we should get strawberry milk. I think of the path—through the embassy’s little garden, where the trees are tall enough to admire but not too wide to hug.

I can hug trees and do all sorts of silly things with Fatim. I say yego. She remembers the important words.

But she’s never usually this quiet. She talks—sometimes about the geopolitics of the Emirates, sometimes about tung tung tung sahur or brainrot.

Tonight, she randomly bursts forward, skipping.

And honestly, I like that.

After such a mentally exhausting gathering—we discussed Jesus’ early life, compared the Gospels, debated his death, and wrestled with big questions—I figured I didn’t need to talk either.

Besides, the road is quiet now. Apart from the occasional electric bike that glides by like a cat, we’re truly alone.

We pass through the garden, Fatim still skipping ahead. Her—black dress? Or is it an abaya? I don’t know—flying a bit in the dark. It’s a beautiful night. My gut was wrong. I look at the tree on my right and hug it. The skipping stops until I finish my hug. Then she goes on.

She’s already across from the library, crossing the road, but I have to wait for a convoy to pass. Most likely the president. Multiple black Toyota V8s breeze by, blowing my shirt to the left. I count nine—maybe ten. I don’t know.

By the time I reach the station, she’s already checking out two Mukamira strawberry milk cartons and a small paper bag—probably cookies.

I turn and playfully skip home. How the turntables. I look back, and she’s quite far behind. I rest on the little steps under the embassy gate and watch her come up. The narrow lane along the fence is dark. Against her black attire, she’s just a shadow. A happy, familiar, comforting shadow that just bought me strawberry milk.

She stands about three meters away, probably expecting me to sit up and head home. But I’m feeling pretty chill where I am. So I fixate on where I think her eyes are. The standoff lasts a minute. Or two. Or five. I don’t really know. Until she gives up and comes to sit beside me.

I lean on the fence to show her my smug face and say poule mouillée—chicken. But that’s when I see it.

A car, headlights on, comes up from the public library lane onto the main road. The light hits her face: that round face and familiar smile—the exact look I expected. Except for her eyes.

It lasts a fraction of a second, but the image might as well be tattooed on my imboni. And suddenly the stillness and heaviness of the night return.

As if to change the subject of a conversation we never had, she hands me my carton. I press a straw in and sip it, almost performatively. Maybe I didn’t see it?

She’s not okay.

And for the first time since I moved here, I struggle to ask her something. Maybe because I’m not sure how she’ll respond to my nosy self. Maybe because I can’t handle hearing the kind of pain that terrifies such lively eyes. Deep brown. Always open. They don’t shy away. They see. They listen. Seeing them nearly teary—urgh.

Or maybe because I know exactly what I saw.

And I’m not sure I can have that conversation. I would rather die.

She picks a cookie and nibbles on it. Cookies. I knew it. I do the same. I take a bite and look ahead—Kigali Public Library. I have a book I need to return. How much is the fine? Is it 300 a day for four months? That’s like… 30 days multiplied by—

I can still see her eyes. And my calculations fall apart. I try again, but it’s no use. So, before I talk myself out of it—

“What’s wrong?”

The question hangs, thick and heavy, like gas weighing on my lungs.

An annoyingly loud truck creeps along the main road. It probably drowned out my question. I wait for it to pass. I pick another cookie. As I fidget with the paper bag, I steal a glance in her direction—but her profile is dark, almost black, like a mysterious character in a manga.

I question whether I really saw what I saw. But even after the truck is long gone, and the only person in sight is a policeman 500 metres away, I still can’t bring myself to ask again.

Once my guts are nearly dissolved by all the churning—shredding, really—I get up, grab the cookie bag, and start walking home. She follows. Then walks beside me. And by the time we’re passing Sandy’s, she’s slightly ahead. I have to quicken my pace to keep up.

I notice her sail — tonight it simply drapes over her, not its usual perfect tuck along the ear. And the side of her face is missing its usual glow. From toner? Serum? Moisturiser? I don’t know. But she’s not okay.

My instinct is to stretch my arms and hug her. Or at least hold her hand. But I’m never sure where the line is. Or what anything means. Who knows if a hug means the same thing to her as it does to me?

Isn’t it enough that we take walks and hang out?

My gaze drops to her Sambas. The rhythm of her steps. The subtle sound. The whoosh of her abaya—fine, dress. I’ll ask what the real name is at some point. Maybe.

Our gate is close. I can feel my chance to ask slipping away.

We enter the courtyard. Slipping faster. She’s headed for her place now. I know that once she’s inside, I won’t have the courage to knock again. Almost gone.

Keys jingle in her hand.

“Fatim?”

“Oui.”

I can’t get myself to say it. My stomach churns again. I would rather die than come up with words to comfort a grieving person. But I want to.

I feel the paper bag in my hand. So I reach in and find the last cookie. I hand it to her. She smiles, takes a bite, then turns around and opens her door.

Coward!.

I’ll just—

And before she disappears behind her curtains—

“Merci beaucoup. I feel so much better now, à cause de toi.”

Door closes.

Because of me?

What have I done?

I stand there, baffled. Far longer than I can remember. Long enough for the night to turn cool. And longer. Until the cat startles me.

I fetch my keys and go in.

I would rather die than come up with words to comfort a grieving person. But maybe I didn’t need to. Maybe we didn’t need to talk tonight.

All the words we’ve shared on bright nights are enough to carry us through the dark ones.

I go inside and eat my mango plain. She’ll probably show me the recipe sometime this week.

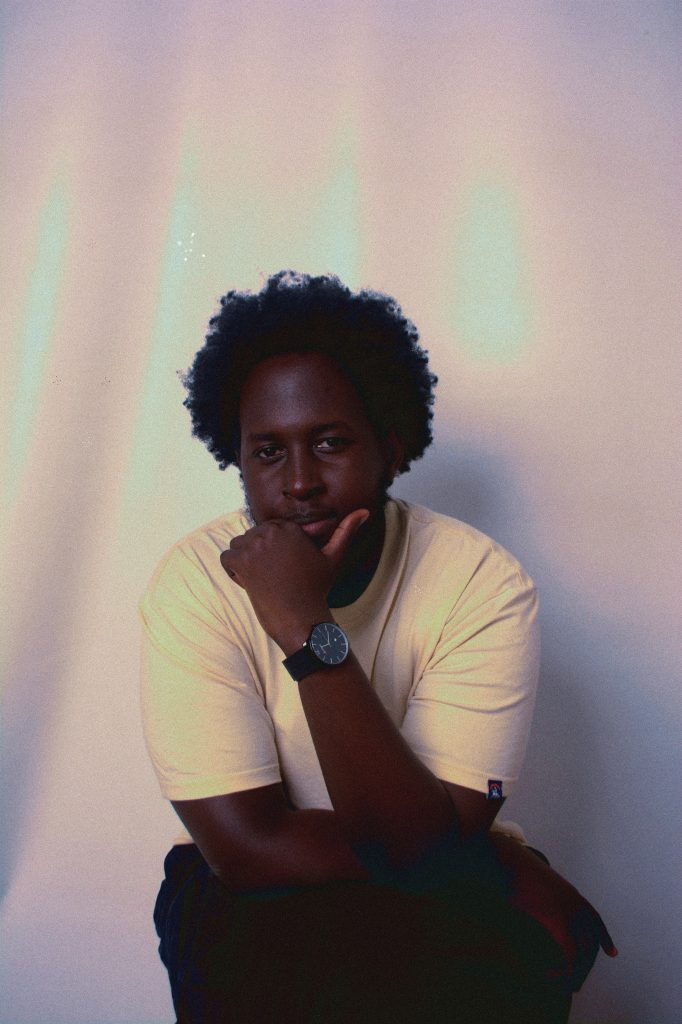

Mutabazi I. Willy Christian (known as Kraft Mutabazi) is a Rwandan playwright, poet, and lyricist whose work pulses with the rhythms of Kigali. Since 2023, he has written and directed two original stage dramas for 7+ Ministries, as well as producing. As of lately, his pieces explore identity and belonging through tightly woven narrative and verse, often debuting in community workshops and open-mic salons.

6 comments

Wow! Cookies in Kacyiru 🥺🥺🥺

sooo good. I love it 😭😭😭

Wish I had chapter 2

I’m real glad you loved it! But I do suck at making sequels. We’ll just write more stories

This definitely deserves to be developed into a novel. We need powerful Rwandan fiction like this! Kudos, Willy!

Yes Dominique, I’m trying to write a novel myself. But it takes quite sometime. Thank you for reading!

Fiction you say? Sounds real to me and for that i salute the writer.

I appreate your Salute baho🙏